Land Ownership – What Does 40 Acres Look Like? How much land is 40 Acres?

In the parlance of land ownership and describing a piece of property, the terms “40” and “40 acres” are heard probably as much as any others. We’ve all heard of a farmer referring to the “lower 40” in a movie or elsewhere. 40 acres is a good place to start, if you’re trying to get a general feel for the size of land parcels.

First, a little history on land surveying systems, or the means by which land is legally subdivided, so that we both know “That is your land; this is mine.”

In the United States, we have two “systems” for subdividing land: 1. Metes and Bounds, and 2. The Public Land Survey System.*

Metes and Bounds

Think of taking your compass and a really long measuring tape outside and using them to describe the boundary of any piece of ground. Maybe a part of your front yard. You’ll take note of directions and distances of the lines that make up the sides of the parcel. The directions and distances of lines are METES. Along the way, you might take note of markers or physical features (a tree, a rock, a garden gnome, etc.) that help you describe your subject area. The markers are the BOUNDS.

For instance, “Starting at the mailbox, travel 120 feet at a bearing of 90 degrees (due east), to the corner of the house.” The mete is the 120 feet at 90 degrees. The bounds are the mailbox and the corner of the house.

To complete your description of the parcel, you’ll continue taking compass readings and measurements, and you’ll continue noting physical features, until you finally arrive back at the mailbox. Then, you’ve completed a METES AND BOUNDS description of that tract of land. Pretty simplistic example, but this really is what a metes and bounds survey system looks like; although, usually with much longer distances. As far as the bounds go, though, these aren’t bad examples. In the real world, trees, rocks, you-name-it have been commonly used throughout history. Hopefully, the description of the property will include some relatively permanent and immovable monuments, such as iron pins, known official survey markers and other bounds/physical features that will stand up to time.

Metes and Bounds is the surveying system that came over from England to the original thirteen colonies. Today, those thirteen states, as well as Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Texas, Tennessee, Vermont, West Virginia and parts of Ohio use Metes and Bounds. Texas uses it, because Texas was it’s own country before joining the U.S.

Anyway, for those states and those parts of Ohio, a land ownership map shows irregularly shaped and sized parcels, all described legally using the metes and bounds system.

This ownership map from Jackson County, Georgia provides an excellent example of the irregularity of tract shapes and sizes that you find in the Metes and Bounds states and parts of Ohio.

Public Land Survey System

When the Revolutionary War with England ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the U.S. suddenly had title to a whole bunch of high-value dirt, known then as the Northwest Territory. We know it today as Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota.

The Second Continental Congress, then governing the newly-independent U.S., saw the sale of these lands as a much-needed source of revenue for the new nation. But, how do you put essentially the entire Midwest of the U.S. up for sale all at once? How do you break it up into tracts that you can describe individually and sell? The answer came with the enactment of the Land Ordinance of 1785, which established what we today call the Public Land Survey System, or PLSS.

Without getting too involved at this point, the PLSS breaks up the land in the “30 Public Land States” (roughly 72% of the area of the U.S.) into many, many large squares called “townships.”

In discussing townships, we are close to talking about what 40 acres looks like. It’s a lot easier to do in the PLSS than it is in Metes and Bounds, as you’ll see in a moment.

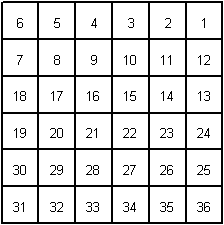

A “Congressional” township is a big square, 6 miles by 6 miles. Within that township, are 36 “sections,” each 1 mile square. They are numbered, starting with the section in the northeast corner. Sections are numbered horizontally. When you reach the end of a line of sections, you drop down. You don’t go back to the eastern end. Sections 1 through 36, ending with the section at the southeast corner of the township.

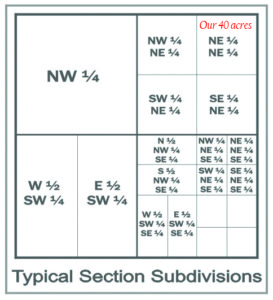

Now, our 40 acres…

Okay, so each of those sections, which as I noted are one mile square, contains 640 acres. So, let’s take just the northeast quarter of that section. It is a 1/2 mile by 1/2 mile and contains 160 acres. Then, let’s take just the northeast quarter of that quarter-section. It’s 1/4 mile by 1/4 mile. IT contains, you guessed it, 40 acres.

Let’s say our section is number 16, we could then describe our 40 acres as: the Northeast Quarter of the Northeast Quarter of Section 16, containing 40 acres.

Remember that a 40-acre square, such as we are discussing here, is 1/4 mile on each side. So, if you walk the perimeter of the 40, you will have traveled one mile. Hopefully, that helps you get a feel for the size of a 40.

I don’t want to get bogged down here on how you describe the particular township in which the section lies. It has to do with the PLSS on a much larger scale. Just know that every township in the PLSS has its own unique “address,” so that no two townships or two sections, for that matter, are described exactly alike. Let’s leave it at that, for now. Maybe we’ll get into it more fully another day, or with an edit to this post later. You can certainly Google it.

Now, as you might imagine, land ownership maps in the states that use PLSS look very different from the metes and bounds states/areas. In those 30 PLSS states, the map will look more like a collection of blocks, with boundaries generally running north/south and east/west.

Have you ever played the video game Tetris? It sort-of looks like a Tetris screen.

In this land ownership map, you can see several 40-acre blocks, which are actual 40’s in Montgomery County, Alabama that people and/or companies own.

When you fly over the Midwest and Great Plains, you can actually see the blocks on the ground, with their trademark circular center-pivot irrigation fields. Pretty cool, really.

So, here’s how the one-square-mile sections would be arranged in a typical township:

Here’s how an individual section might be divided:

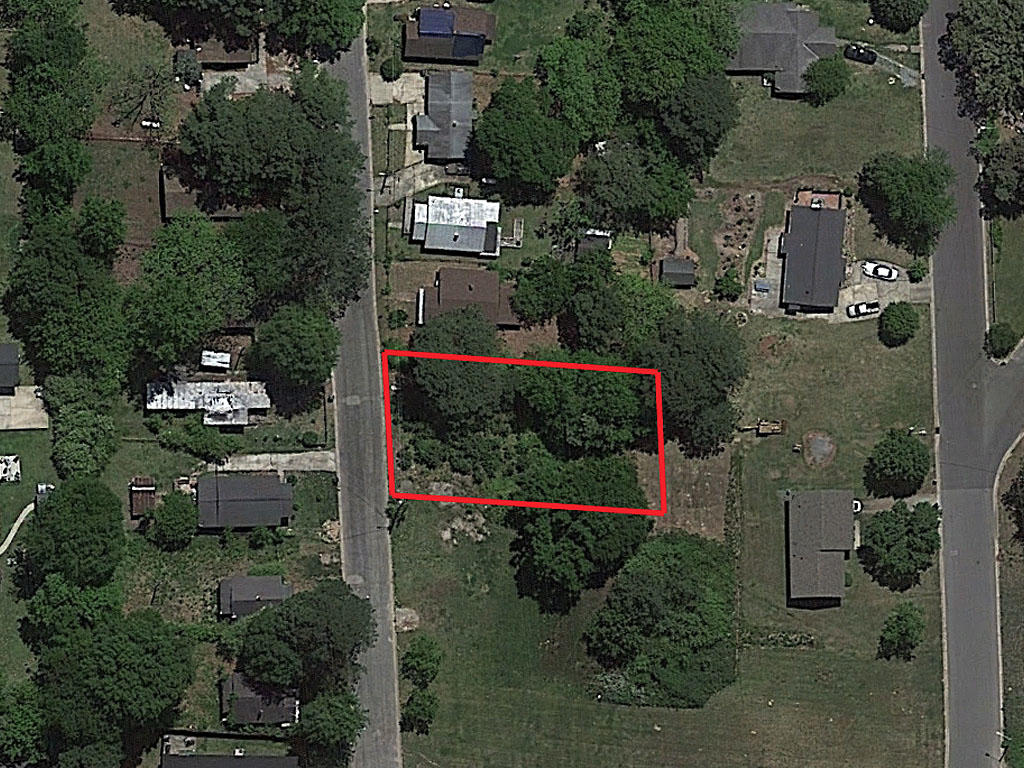

Here’s what 40 acres looks like from 10,000 feet:

I’m presenting all of this so that as you begin to look at land investment, if you do, you can get a general feel for what 40, 80 or 100 or more acres might look like. This is just a very typical example, and few properties fit the “typical” description. A good starting point is all it is.

What does 1 Acre look like? How much land is 1 Acre?

One acre is equal to 43,560 square feet, no matter what the shape of the parcel.

Here’s what one acre looks like:

What does 10 Acres look like? How much land is 10 Acres?

Ten acres is equal to 435,600 square feet, no matter what the shape of the parcel.

Here’s what ten acres looks like:

How many acres are in a 100′ by 100′ lot?

The average home lot in the United States is about 1/4-Acre (about 10,000 square feet, which is the area in a 100′ by 100′ lot).

This is an example of a quarter-acre lot:

Questions? Comments? Let me know. This isn’t a Wiki page, but, where I need clarification or correction, I’m open to it.

(*) The third method for subdividing land is an actual survey. Only licensed professional surveyors perform surveys. My discussion above is more about the two “systems” that are in use in the various states (and parts of Ohio) and really focuses on providing a feel for what 40 acres looks like. Surveys are, of course, common in practice and provide the best of all worlds, in terms of defining the boundary of a tract of land.

On more than a few occasions, I’ve needed surveys on tracts in Alabama and Mississippi, both PLSS states. PLSS is a great framework, but sometimes we need clarification on where a section line or some other line should actually lay on the ground. A licensed professional surveyor is the only individual qualified to provide those answers definitively.

There are plenty of references on the Internet about the science and art of the professional surveyor. It’s a fascinating field with a rich, rich history in itself. Maybe a good topic for a future post.

Bucky Henson

[email protected]

334-412-2487

Hello, and thanks for visiting NatVest.com.

My name is Bucky Henson. I am Qualifying/Responsible Broker and President of NatVest LLC.

Among other things, I’ve worked with natural investment properties (timberland, farms & other real estate) for about 30 years.

NatVest.com is my blog directly intended to present the idea of landownership to people who haven’t previously considered land as an investment option and as a way of life. It is both.

We hope to present a wide array of perspectives of land ownership and stewardship that will, hopefully, spark interest and interaction about the topic.

We welcome you and, more so, welcome your input and participation in the discussion.

I can be reached at [email protected] or on my cell: 334-412-2487.

And, by the way, I am now taking listings for properties for sale in Alabama and Georgia, so please give me a call, if I can help you.

Finally, I also handle timber sales, buy standing timber and help people evaluate their options on timber sales. So call or write if I can help with any of your timber sales needs.

Hello, and thanks for visiting NatVest.com.

My name is Bucky Henson. I am Qualifying/Responsible Broker and President of NatVest LLC.

Among other things, I’ve worked with natural investment properties (timberland, farms & other real estate) for about 30 years.

NatVest.com is my blog directly intended to present the idea of landownership to people who haven’t previously considered land as an investment option and as a way of life. It is both.

We hope to present a wide array of perspectives of land ownership and stewardship that will, hopefully, spark interest and interaction about the topic.

We welcome you and, more so, welcome your input and participation in the discussion.

I can be reached at [email protected] or on my cell: 334-412-2487.

And, by the way, I am now taking listings for properties for sale in Alabama and Georgia, so please give me a call, if I can help you.

Finally, I also handle timber sales, buy standing timber and help people evaluate their options on timber sales. So call or write if I can help with any of your timber sales needs.